Cinema

Surrealist of Cinema

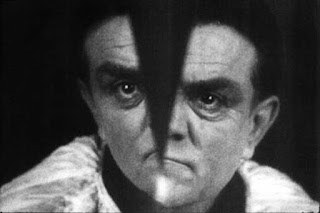

Surrealist cinema

is a modernist approach to film theory,

criticism, and production with origins in Paris in the 1920s. Related to Dada

cinema, Surrealist cinema is characterised by juxtapositions, the rejection of

dramatic psychology, and a frequent use of shocking imagery. The first

Surrealist film was The Seashell and the Clergyman from 1928, directed

by Germaine Dulac from a screenplay by Antonin Artaud. Other films include Un

Chien Andalou and L'Age d'Or by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí;

Buñuel went on to direct many more films, with varying degrees of Surrealist

influence.

Surrealism was an avant-garde art movement in Paris from 1924 to

1941, consisting of a small group of writers, artists, and filmmakers,

including André Breton (1896–1966), Salvador Dali (1904–1989), and Luis Buñuel

(1900–1983). The movement used shocking, irrational, or absurd imagery and

Freudian dream symbolism to challenge the traditional function of art to

represent reality. Related to Dada cinema, Surrealist cinema is characterised

by juxtapositions, the rejection of dramatic psychology, and a frequent use of

shocking imagery.

Critics

have debated whether 'Surrealist film' constitutes a distinct genre.

Recognition of a cinematographic genre involves the ability to cite many works

which share thematic, formal, and stylistic traits. To refer to Surrealism as a

genre is to imply that there is repetition of elements and a recognizable,

generic formula which describes their makeup. Several critics have argued that,

due to Surrealism's use of the irrational and on non-sequitur, it is impossible

for Surrealist films to constitute a genre or a style. In his 2006 book Surrealism and Cinema, Michael

Richardson argues that surrealist works cannot be defined by style or form, but

rather as results of the practice of surrealism. Richardson writes: "Within popular

conceptions, surrealism is misunderstood in many different ways, some of which

contradict others, but all of these misunderstandings are founded in the fact

that they seek to reduce surrealism to a style or a thing in itself rather than

being prepared to see it as an activity with broadening horizons. Many critics

fail to recognized the distinctive qualities that make up the surrealist

attitude. They seek something – a theme, a particular type of imagery, certain

concepts – they can identify as 'surrealist' in order to provide a criterion of

judgement by which a film or art work can be appraised. The problem is that

this goes against the very essence of surrealism, which refuses to be here

but is always elsewhere. It is not a thing but a relation between

things and therefore needs to be treated as a whole.

DADA ROOTS

"Dada was a movement that

attracted artists in all media. It began around 1915, as a result of artists'

sense of the vast, meaningless loss of life in World War I. Artists in New York, Zurich, France, and Germany proposed to sweep aside

traditional values and to elevate an absurdist view of the world. They would

base artistic creativity on randomness and imagination. Max Ernst displayed an

artwork and provided a hatchet so that spectators could demolish it. Marcel

Duchamp invented "ready-made" artwork, in which a found object is

placed in a museum and labeled; in 1917, he created a scandal by signing a urinal

"R. Mutt" and trying to enter it in a prestigious show. Dadaists were

fascinated by collage, the

technique of assembling disparate elements in bizarre juxtapositions. Ernst,

for example, made collages by pasting together scraps of illustrations from

advertisements and technical manuals.

Under the leadership of poet Tristan Tzara, Dadaist publications,

exhibitions, and performances flourished during the late 1910s and early 1920s.

The performance soirée

included such events as poetry readings in which several passages were

performed simultaneously. On July 7, 1923, the last major Dada event, the Soirée du 'Coeur à Barbe' (Soirée

of the ' Bearded Heart' ), included three short films: a study of New York by

American artists Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand, one of Hans Richter's Rhythmus abstract animated works,

and the American artist Man Ray's first film, the ironically titled Le retour à

la raison (Return to Reason). The element of chance certainly entered into the

creation of Retour à la raison,

since Tzara gave Ray only twenty four hours' notice that he was to make a film

for the program. Ray combined some hastily shot live footage with stretches of "Rayograms". The soirée proved a mixed

success, since Tzara's rivals, led by poet Andre Breton, provoked a riot in the

audience.

THE SURREALISTS

The surrealist image could be either

verbal or pictorial and had a twofold function. First, images that seem

incompatible with each other should be juxtaposed together in order to create

startling analogies that disrupt passive audience enjoyment and conventional

expectations of art. This technique was perhaps an influence of Soviet montage theory, with which the

surrealists were familiar. Second, the image must mark the beginning of an

exploration into the unknown rather than merely representing a thing of beauty.

The surrealist experience of beauty instead involved a psychic disturbance, a

"convulsive beauty" generated by the startling images and the

analogies they create in the mind of the viewer.

"Surrealism resembled

Dada in many ways, particularly in its disdain for orthodox aesthetic

traditions. Like Dada, Surrealism sought out startling juxtapositions. Andre

Breton, who led the break with the Dada is it and the creation of Surrealism,

cited an image from a work by the Comte de Lautreamont: "Beautiful as the unexpected meeting, on a dissection table, of a

sewing machine and an umbrella." The movement was heavily influenced

by the emerging theories of psychoanalysis. Rather than depending on pure

chance for the creation of artworks, Surrealists sought to tap the unconscious

mind. In particular, they wanted to render the incoherent narratives of dreams

directly in language or images, without the interference of conscious thought

processes.

Rose Hobart

Germaine Dulac, who had already worked extensively in regular

feature filmmaking and French Impressionism, turned

briefly to Surrealism, directing a screenplay by poet Antonin Artaud. The

result was La coquille et le clergyman (The Seashell and the Clergyman,

1928), which combines Impressionist techniques of cinematography with the

disjointed narrative logic of Surrealism. A clergyman carrying a large seashell

smashes laboratory beakers; an officer intrudes and breaks the shell, to the

clergyman's horror. The rest of the film consists of the priest's pursuing a

beautiful woman through an incongruous series of settingsThe initial screening

of the film provoked a riot at the small Studio des Ursulines theater, though

it is still not clear whether the instigators were Artaud's enemies or his

friends, protesting Dulac's softening of the Surrealist tone of the scenario.

With The Seashell and the Clergyman,

Dulac overhauls narrativity entirely and presents us with pure feminine desire,

intercut against masculine desires of a priest. Above all, Dulac is responsible

for "writing" a new cinematic language that expressed transgressive

female desires in a poetic manner.

Cornell avoided giving

more than a hint as to what the original plot, with its cheap jungle settings

and sinister turbaned villain, might have involved. Instead, he concentrated on

repetitions of gestures by the actress, edited together from different scenes;

on abrupt mismatches; and especially on Hobart's

reactions to items cut in from other films, which she seems to "see" through false eye line

matches. In one pair of shots, for example, she stares fascinated at a

slow-motion view of a falling drop creating ripples in a pool. Cornell

specified that his film be shown at silent speed (sixteen frames per second

instead of the usual twenty-four) and through a purple filter; it was to be

accompanied by Brazilian popular music. (Modern prints are tinted purple and

have the proper music.)"

Rose Hobart seems to have had a single screening in 1936, in a

New York gallery program of old films treated as "Goofy Newsreels".

Its poor reception dissuaded Cornell from showing it again for more than twenty

years.

"Whereas the French Impressionist filmmakers worked within the

commercial film industry, the Surrealist filmmakers relied on private patronage

and screened their work in small artists' gatherings. Such isolation is hardly surprising, since Surrealist

cinema was a more radical movement, producing films that perplexed and shocked

most audiences.

Surrealist cinema was directly linked to Surrealism in literature and

painting. According to its spokesperson, Andre Breton, "Surrealism [was]

based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of association,

heretofore neglected, in the omnipotence of dreams, in the undirected play of

thought." Influenced by Freudian psychology, Surrealist art sought to

register the hidden currents of the unconscious, "in the absence of any

control exercised by reason, and beyond any aesthetic and moral

preoccupation."

Automatic writing and

painting, the search for bizarre or evocative imagery, the deliberate avoidance

of rationally explicable form or style - these became features of Surrealism as

it developed in the period 1924-1929. From the start, the Surrealists were

attracted to the cinema, especially admiring films that presented untamed

desire or the fantastic and marvelous (for example, slapstick comedies,

Nosferatu, and serials about mysterious supercriminals). Surrealist cinema is

overtly anti-narrative, attacking causality itself. If rationality is to be

fought, causal connections among events must be dissolved, as in The

Seashell and the Clergyman.

The hero gratuitously shoots a child (L’Âge

d’or), a woman closes her eyes only to reveal eyes painted on her eyelids

(Ray's Emak Bakia, 1927), and - most famous of all - a man strops a razor and

deliberately slits the eyeball of an unprotesting woman (Un chien andalou). An

Impressionist film would motivate such events as a character's dreams or

hallucinations, but in these films, character psychology is all but

nonexistent. Sexual desire and ecstasy, violence, blasphemy, and bizarre humor

furnish events that Surrealist film form employs with a disregard for

conventional narrative principles. The hope was that the free form of the film

would arouse the deepest impulses of the viewer.

The style of Surrealist cinema

is eclectic. Mise-en-scene

is often influenced by Surrealist painting. The ants in Un chien andalou come from Dali's pictures; the pillars

and city squares of The Seashell and the Clergyman hark back to the

Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico. Surrealist editing is an amalgam of some

Impressionist devices (many dissolves and superimpositions) and some devices of

the dominant cinema. The shocking eyeball slitting at the start of Un chien

andalou relies on some principles of continuity editing (and indeed on the

Kuleshov effect). However, discontinuous editing is also commonly used to

fracture any organized temporalspatial coherence. In Un Chien andalou,

the heroine locks the man out of a room only to turn to find him inexplicably

behind her. On the whole, Surrealist film style refused to canonize any

particular devices, since that would order and rationalize what had to be an

"undirected play of thought."

The fortunes of Surrealist cinema shifted with changes in the art

movement as a whole. By late 1929, when Breton joined the Communist Party,

Surrealists were embroiled in internal dissension about whether communism was a

political equivalent of Surrealism. Buñuel left France

for a brief stay in Hollywood and then returned

to Spain.

The chief patron of Surrealist filmmaking, the Vicomte de Noailles, supported

Jean Vigo's Zéro de conduite (1933), a film of Surrealist ambitions, but then

stopped sponsoring the avant-garde. Thus, as a unified movement, French

Surrealism was no longer viable after 1930. Individual Surrealists continued to

work, however. The most famous was Buñuel, who continued to work in his own

brand of the Surrealist style for 50 years. His later films, such as Belle de

jour (1967) and Le charme discret de la bourgeoisie (1972), continue the

Surrealist tradition." In 1947 Hans Richter released Dreams That Money Can

Buy, seven short episodes that examine the unconscious, written by and

featuring Richter, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Fernand Léger, Max Ernst (1891–1976),

and Alexander Calder (1898–1976). Besides Bunuel's work, this is the last

official surrealist film.

After World War I,

France looked toward avant-garde cinema to make its mark against Hollywood.

Impressionism, which focused on psychological realism, naturalism, and

symbolism, became the dominant French film movement. The surrealists, many of

whom were avid film spectators, despised impressionism, but they admired

lowbrow American serials and slapstick comedies. Breton and his fellow

surrealists found the modernism of Hollywood

cinema an exciting medium in its infancy, unencumbered by a conscious artistic

tradition.

Though dada rejected

cinema as a medium of impressionism, a few dada artists experimented with

filmmaking. The Rhythmus films (1921, 1923, 1925) of Hans Richter

(1888–1976) and Symphonie diagonal (Symphonie diaganale, 1924) of

Viking Eggeling (1880–1925) attempted to establish a universal pictorial

language using abstract geometric shapes in rhythmic movement. Duchamp produced

Anémic

cinema (Anemic Cinema, 1926), in which he filmed a

spinning spiral design intercut with a spinning disc containing French phrases.

Man Ray (1890–1976) filmed Le Retour à la raison ( Return to Reason ,

1923) using an avant-garde photography technique he pioneered and named the

"rayograph." Though cubist artist Fernand Léger (1881–1955) and

filmmaker Dudley Murphy (1897–1968) were not members of dada, their

collaborative abstract film Ballet mécanique (1924) is often discussed

in relation to these films because of its similar visual style and Léger's aim

to exasperate viewers. Richter's Vormittagsspuk (Ghosts

Before Breakfast, 1928) merged slapstick and dada to create a highly

entertaining six-minute film.

GERMAINE

DULAC

b. Amiens, France, 17 November 1882, d. 20

July 1942

A director, writer, and film theorist,

Germaine Dulac was the first female avant-garde filmmaker in France. She was

never an official member of the surrealist movement, but her theory of

"pure cinema" shared similar goals and ideals to those of surrealism.

Though many of Dulac's films were highly successful commercial narratives

(serials and melodramas), her best moments evoked emotion without resorting to

dramatic devices. Her skill of tapping into the unconscious processes of her

characters and her viewers' perceptions linked her thematically to the

surrealists. Dulac's goal of "pure cinema" centered on producing films that were independent of literary, theatrical, or other artistic influences. Throughout her film career, she experimented with new ways of presenting characters' inner emotions and exploring their psychological states through cinematic means without ever being tied to one particular avant-garde movement. Her editing techniques have been compared to those of D. W. Griffith, creating an unconscious reaction in the mind of the viewer. She was also very skilled in incorporating music into her later sound films to create visual and aural rhythms.

Dulac's pre-film background involved feminism and journalism, and her films return time and again to themes of femininity. Her films directly challenge the romantic perceptions, metaphorical mythologies, and social constructions of womanhood. She distinguishes between male and female subjectivity in La Mort du soleil ( The Death of the Sun , 1922) and focuses on female subjectivity in La Souriante Madame Beudet ( The Smiling Madame Beudet , 1922), in which she uses a number of special effects, lighting, and editing techniques to represent directly the protagonist's thoughts and imagination.

In 1927 Dulac came across surrealist Antonin Artaud's screenplay for La Coquille et le clergyman ( The Seashell and the Clergyman ), which he had deposited at a film institute due to lack of funds to produce it. The surrealists considered Dulac, who was already well established in the Parisian avant-garde film community, to be strictly impressionist—too loyal to traditions of naturalism and symbolism for their liking. Dulac followed Artaud's script closely in her 1928 film, only changing a few practical elements when necessary. Yet Artaud claimed she had butchered his script, and he staged a riot during the premiere screening. Although André Breton had expelled Artaud from the surrealists the previous year, the group joined in the riot, screaming profanities and halting projection of the film. La Coquille et le Clergyman was removed from the program and its surrealism was overshadowed that year by Dali and Buñuel's Un Chien andalou ( An Andalusian Dog , 1928). Though the surrealists themselves rejected the film, most critics today consider La Coquille et le Clergyman to be the first surrealist film.

Erin Foster

The

Surrealist film Un

Chien andalou (An Andalusian Dog, 1929)

was a collaboration between filmmaker Luis Buñuel and painter Salvador Dali.

surrealistic dream

sequence in Spellbound (1945). All other attempts Dali made at

filmmaking proved unsuccessful, and he soon after returned to painting.

Cinema came relatively

late in the surrealist movement, and it was never fully utilized, much to the

regret of Breton. This was probably due to the actual practicalities of

filmmaking, which were inherently opposed to the surrealist ideals of chance

and automation. Buñuel was the only surrealist to have gotten seriously

involved in the technical and practical aspects of the medium, which may have

also helped lead him to breaking with the movement. Another limiting factor in

surrealist film experimentation was that amateur filmmaking was extremely

expensive until after World War II; afterward, cheaper film equipment became

available, but by then the surrealist movement had disbanded. In 1947 Hans

Richter released Dreams That Money Can Buy , seven short episodes that

examine the unconscious, written by and featuring Richter, Man Ray, Duchamp,

Léger, Max Ernst (1891–1976), and Alexander Calder (1898–1976). Besides

Buñuel's work, this is the last official surrealist film.

Though surrealist film was limited, the

artistic ideals of surrealism have been influential for a number of filmmakers.

American experimental filmmakers like Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage, and Kenneth

Anger utilized the surrealistic approach to push the boundaries of film

representation and shock audiences out of passive spectatorship. Deren's Meshes

of the Afternoon (1943) uses a repetitive, loosely narrative structure and

Freudian symbolism to examine female subjectivity in cinema. Brakhage sometimes

painted or scratched abstract designs directly onto celluloid, and films of his

such as Dog Star Man (1962) use repetitive or unrelated imagery in ways

that often alienate viewers. In Anger's dreamlike Fireworks (1947), the

director uses violent imagery to explore his own homosexuality. The surrealist

aesthetic also is apparent in animation, particularly in Japanese animé and in

the work of eastern European animators like Jan Svankmajer. European auteurs

like Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, and Wim Wenders also owe a debt to

surrealism. American filmmakers David Lynch and Terry Gilliam and Canadian

David Cronenberg also rely heavily on surrealistic imagery, ironic

juxtapositions, misleading narrative devices, and Freudian symbolism to shock,

confuse, and challenge spectators.

FILM FORM AND STYLE

- Use of a variety of conventional devices and techniques without wanting to be tied down to

- Any predictable form. Dissolves, superimposition's + some traditional editing conventions.

- Point of view shots , a mixture of discontinuity and continuity editing and the unexpected

- Juxtaposition of images were often used to shock and disorientate the spectator.

Mise - en - Scene was

often influenced by surrealist paintings, e.g. the ants in 'Un Chien'

from Dali's paintings, the pillars and city squares in 'The seashell and the Clergyman' from

De Chirico's paintings. Objects/things often positioned out of

context - free to live a life of

their own and be shown in a new light.

Breton referred to beauty ' as the unexpected

meeting, on a dissection table, of a sewing

machine

and an umbrella'.

Impressionism

was the first art movement to be categorized as modernist. Impressionist

painters focused more on the act of seeing then on the subject. They purposefully

made the viewer aware of the brush strokes rather then the pretense of

attempting to replicate reality.

Cubism focused

on playing with perspective, where the artist would show the viewer several

different perspectives of one subject. This sentiment is most well known for

Pablo Picasso. It can also be seen in literature with a book like Faulkner’s As

I Lay Dying.

Expressionism

focused on manipulating physical reality as a means to reflect the emotional

state of the artist or the main character.

Futurism focused

displaying speed and movement. A Woman Descends A Staircase is the

best example of this sentiment. The futurists loved modern technology and

images of the future. I would imagine that they would have loved modern action

movies, that is if most of the futurists weren’t killed in WWII.

Fauvism, a

little known movement, focused on presenting the viewer with a strong pallet of

color.

Surrealism was a

movement that played with the very means of representation. Salvador Dali’s

works appear to exist in a universe where the physical properties of matter are

amorphous, where the subject of representation is up to interpenetration.

Magritte was far more blatant with his examination between reality and

representation. Since motion pictures is a more photographic medium, Surrealist

filmmakers like Bunuel played with narrative conventions, spacial and temporal

relations, and the social relations between characters that defied convention

and logic.

“Los

Olvidados,” which translates to “the forgotten ones,” was one of the series of

films Bunuel made after a fifteen-year hiatus from film that ended shortly

after his move to Mexico in the 1940s. Bunuel had been exiled from Spain after

the Spanish Civil War, having been a member of the Spanish Republic, and

despite the controversy around “L’Age d’or” (and Dali) and the surrealistic

nature of even his documentary, “Land without Bread,” MGM studios in Hollywood

offered him a contract. He made no films whist there. In Mexico, the “Golden

Age of Mexican Cinema” (1930s-50s) was in full swing. Bunuel was attracted to

the flourishing industry, the product of which was not seen in the U.S. though

exported to other Latin countries well, and worked there for 15 years (until

the 1960s). Surprisingly, during this period his career was in the commercial

film industry. “Los Olvidados” was the film marked his return to the

international film scene. Bunuel was uneasy about its release, predicating that

the Italian Neo-Realist influences evident in his new style would be

interpreted as a betrayal of his Surrealism roots by friends and colleagues. In

fact, the film was received with acclaim, and is considered on the key films in

Latin American and World cinemas. I found it interesting that the opening

sequence served almost like a reminder to the world that Mexico exists, too,

and that it’s problems resemble those of European countries, too. This move,

and many other gestures in the film, including the powerful dream sequence, put

the Bunuel twist on neo-realism. Surrealism’s link with dreams actually

supported the presence of organic and realistic symbolism and metaphors found

in recurrent imagery, such as chickens. Early on in “Los Olvidados” a guiding

metaphor is established during a cruelly violent scene, in which the gang

of boys attack the blind, elderly fascist. The high camera angle used

here and throughout the film, visually reiterates the idea of an old Spanish

saying that translates loosely to “a blind man’s blows” and points to the idea

of striking blindly. All the characters depicted in the film are vulnerable to

feeling the need to lash out and react, but know not what to or what for, and

in that sense all the strikes and blows of the film are “blind.” In their

desperation there is little difference between Jaibo killing Julian, and Pedro

killing the chickens. Desperation and the almost utter lack of control they

have over their lives lead them to strike against each other, in the attempt of

the oppressed to become the oppressors instead. Chickens are not metaphors for

anything, though they are a running symbol throughout. More than anything, they

are a part of the daily reality of the characters lives, but here their

presence has a surrealist twist, which alerts us that something is off. It’s

only fitting that they be in most realistic and surrealist scenes.

Pedro’s

dream is the most surreal sequence. It depicts a dream in which you’re dreaming

that you’re dreaming and are in the place where you’re sleeping. It plays out

in slow motion, and is rife with edible implications. Unlike in his surrealist

films where the boundaries between dream and reality are barely existent, this

is clearly delineated as a dream, which on the one hand, makes it a

conventional device, but on the other hand, heightens the sense of reality. The

latter is due mainly to the nature and content of the dream being of such a palpable,

physical quality, like a slab of raw meat.

The

way characters are developed as both conventions and realistically human is an

interesting quality that the film implements. For example, all of the

characters have some resonance of reality, but Ojitos stands out for he is both

different and one and the same as the rest. During “milk bath” sequence we

witness the not only the developing affection between him and Metche, but also

his capacity for violence. He is undoubtedly a good and sweet boy, but he will

also strike out in defense. The blind man appears to be more of a convention

than a particular. As a matter of fact, Bunuel was not fond of blind men, and

had a history of roughing them up in his films (as in the opening sequence of

“L’age d’or”) because they are conventional objects of piety and charity, and

more importantly, of self-satisfied benefaction. He puts a spin on this one,

making the blind man a fascist sympathizer.

Surrealism

and Cinema: Un Chien Andalou:

Bunuel

seems to have had a flare for turning conventions against the conventional. The

narrative, like the symbolism and character treatment, uses a typical device

atypically and in a way that seems to have grown organically out of the

circumstances. The narrative frequently employs the use of coincidence,

but with a realistic function. It adds to the sense how just how intertwined

their lives are, how inescapable the forces of one’s life are, that they are

running around in circles, friction is bottled up, and there is a looming sense

of “sooner or later,” as well as an incestuous quality to the way the lives and

affairs are entangled in these slum areas. All of this comes to a head as a

result of an outside force stepping in. Interestingly, the director of the

youth farm is an authority figure, on e of the few in the film, and portrayed

in a positive light. More interesting is that his good gesture of the best

intentions toward Pedro had the unfortunate and immediate consequence of

leading to tragedy. In fact, it’s a double tragedy because the director had

read Pedro right and Pedro was responding positively. This leads us to ask,

what turned the situation sour? Following this thought thread we end up in a

conflict of problemetizing moralizing. Pedro overcompensates for his feelings

of shame and thinks he cannot return to the farm empty handed. Jaibo

overcompensates his feeling of abandonment by turning on anyone he ever called

a friend. When they duel it out, one could see Pedro as the good boy and Jaibo

the bad, yet the film is not melodramatic in this regard. Here the boys are

treated more like opposite heads of the same coin in the sense that both are

products of similar circumstances. In this way, Pedro’s mother is put on their

same level. It’s important to note that despite seeing how morally questionable

she is, we can empathize with her well she retorts to the official’s

condescension, “what could I do?”. In this example, and in other ways the film

puts moralizing on the back burner, taking up instead a stance that things are

not right, hammered home by the protagonist dying among and being equated with

the chickens. Its also present in the difficulty one has in labeling hero and

villain, finding instead a doubling. Jaibo and Pedro even die “together,”

serially back to back, and both are shown as victims, and victimizers also.

"I

Vitelloni" (1953) directed by Frederico Fellini

Fellini, one of the most famous filmmakers, collaborated frequently with

Rossellini, is accredited for writing “Rome, Open City,” and had only had his

first solo directing job, “Lights of Variety,” a year prior to making

“I’Vitelloni” in 1953. The title literally means, “fatted calves,” but is used

metaphorically in the film for the group of young men who are more or less

living off of their families. The term is now used colloquially, and Fellini

can be credited with introducing “paparazzi” into the vernacular. Fellini’s

work was indebted to neo-realism, but is full of his personal touches. In terms

of the narrative, “I’Vitelloni” is a little bit of both. Fellini was actually

from a small seaside town, though on the opposite coast of Italy, and the film

reflects his experiences growing up in a beach town off-season. The

focus is on the location and the locals, those who live there year round.

“I’Vitelloni” has a very interesting narrative structure

that’s worth taking a look at. While it is certainly a story of the place, and

the ocean representing both horizons and barriers, as well as being part of the

logistical reality, the films main interest lies in its narrative structure in

relation to character development. It is an ensemble piece, and the voice-over

narrator speaks in the first person plural as if one of the group, and yet the

question of “who is the narrator?” cannot really be resolved. The P.O.V. of the

film is not with any one character, but it also never strays from the

individuals of the group, and is therefore not omniscient. There is actually

very little to the plot, and what is there is fleshed out by the subjectivity

and focus on events that the individuals of the group experience. For example,

it’s not all that interesting that a womanizer who had to have a shotgun

wedding would cheat on his wife. What is interesting is how the scene plays

out.

Firstly, it assumes Fausto’s P.O.V. As he follows her we

get a good sense of the place, how quite, safe, and dull the town is at night.

The time of the scene is equitable to Fausto’s subjective sense of time, so

that the screen time and his conception of how much time has passed is only

about 3 minutes, but the time that elapsed in the fictional “real time” was

much more, and he was merely unaware of it. Another example would be the

encounter between Leopoldo and the penny-theater actor. There is again a vivid

sense of space, but now the atmosphere, with all the howling wind and looming

shadows, is a bit spooky and reflects Leopoldo’s fear. He is not a afraid as a

result of the weather, but because of what the dialogue with actor represents.

Outwardly, we can surmise that he is afraid of leaving the nest, and of the

actor’s homosexual pass. The latter is not frightening, but is opens up his

fear of the outside world, for Leopoldo is a dreamer not a doer. Unfortunately,

for any chances he may have had for his career, his fear is misplaced onto the

actor. The final sequence takes Moraldo’s P.O.V. Many initially believe that

Moraldo is the narrator, having been the only one to leave and thus be able to

look back upon it. Certainly, Moraldo is most like Fellini himself, but he is

not the narrator. He does, however, provide us with a striking and tender exit

to the story. In a sequence of traveling shots we pass by all in the group as

if on the train and in his head saying his mental farewells to his sleeping

friends.

Both of these films are ensemble pieces, with a

group narrative structure. Neither film is strictly neo-realist, though the

movement heavily influenced both. Fellini came into it via Rossellini, but came

out of it via his own devices and taking his own approaches. Both films are

undeniably stories of the place, and carry with them and vivid sense of the

space. “I’Vitelloni” more so, but neither film has a tight narrative, either.

As is “Bicycle Thieves” the looseness of it lends itself to the realism, in

that it makes the plot more open and the story more permeable to reality, as

well as allowing for a greater exploration of the space. All three films all

seem to deal with themes that involve the vicious circles social classes go in.

Surrealism has long been recognized as having made a major

contribution to film theory and practice, and many contemporary film-makers

acknowledge its influence. Most of the critical literature, however, focuses

either on the 1920s or the work of Buuel. The aim of this book is to open up a

broader picture of surrealism's contribution to the conceptualisation and

making of film. Tracing the work of Luis Buuel, Jacques Pervert, Nelly Kaplan,

Walerian Borowcyzk, Jan vankmajer, Raul Ruiz and Alejandro Jodorowsky, Surrealism

and Cinema charts the history of surrealist film-making in both Europe and

Hollywood from the 1920s to the present day. At once a critical introduction

and a provocative re-evaluation, Surrealism and Cinema is essential reading for

anyone interested in surrealist ideas and art and the history of film.

Surrealism was an avant-garde art movement in

Paris from 1924 to 1941, consisting of a small group of writers, artists, and

filmmakers, including André Breton (1896–1966), Salvador Dali (1904–1989), and

Luis Buñuel (1900–1983). The movement used shocking, irrational, or absurd

imagery and Freudian dream symbolism to challenge the traditional function of

art to represent reality. Related to Dada cinema, Surrealist cinema is

characterised by juxtapositions, the rejection of dramatic psychology, and a

frequent use of shocking imagery.

Critics have debated whether 'Surrealist film'

constitutes a distinct genre. Recognition of a cinematographic genre involves

the ability to cite many works which share thematic, formal, and stylistic

traits. To refer to Surrealism as a genre is to imply that there is repetition

of elements and a recognizable, generic formula which describes their makeup.

Several critics have argued that, due to Surrealism's use of the irrational and

on non-sequitur, it is impossible for Surrealist films to constitute a genre or

a style. In his 2006 book Surrealism and Cinema, Michael Richardson

argues that surrealist works cannot be defined by style or form, but rather as

results of the practice of surrealism. Richardson writes: "Within popular

conceptions, surrealism is misunderstood in many different ways, some of which

contradict others, but all of these misunderstandings are founded in the fact

that they seek to reduce surrealism to a style or a thing in itself rather than

being prepared to see it as an activity with broadening horizons. Many critics

fail to recognise the distinctive qualities that make up the surrealist

attitude. They seek something – a theme, a particular type of imagery, certain

concepts – they can identify as 'surrealist' in order to provide a criterion of

judgement by which a film or art work can be appraised. The problem is that

this goes against the very essence of surrealism, which refuses to be here

but is always elsewhere. It is not a thing but a relation between

things and therefore needs to be treated as a whole.

Surrealists are not concerned with conjuring up

some magic world that can be defined as 'surreal'. Their interest is almost

exclusively in exploring the conjunctions, the points of contact, between

different realms of existence. Surrealism is always about departures rather

than arrivals."

[3]

While there are numerous films which are true

expressions of the movement, many other films which have been classified as

Surrealist simply contain Surrealist fragments. Rather than 'Surrealist film'

the more accurate term for such works may be 'Surrealism in film'.

Film Styles

- British New Wave

- Cinema Novo

- Cinéma vérité

- Film Noir

- French Impressionism

- German Expressionism

- Italian Neorealism

- Nouvelle Vague

- Screwball Comedy

Even

though by 1922, dada was dead, key Dada films were still to come. "In late

1924, Dada artist Francis Picabia staged his ballet Relâche (meaning

"performance called off"). Signs in the auditorium bore such

statements as "If you are not satisfied, go to hell." During the

intermission (or entr'acte), René Clair's Entr'acte was shown, with music by

composer Erik Satie, who had done the music for the entire show. The evening

began with a brief film prologue (seen as the opening segment of modern prints

of Entr'acte) in which Satie and Picabia leap in slow motion into a scene and

fire a cannon directly at the audience. The rest of the film, appearing during

the intermission, consisted of unconnected, wildly irrational scenes. Picabia

summed up the Dada view when he characterized Clair's film: "Entr'acte

does not believe in very much, in the pleasure of life, perhaps; it believes in

the pleasure of inventing, it respects nothing except the desire to burst out

laughing."

Dada artist Marcel Duchamp

made one foray into cinema during this era. By 1913, Duchamp had moved away

from abstract painting to experiment with such forms as ready- mades and

kinetic sculptures. The latter included a series of motor-driven spinning

discs. With the help of Man Ray, Duchamp filmed some of these discs to create Anémic

cinema in 1926. This brief film undercuts traditional notions of cinema as a

visual, narrative art. All its shots show either turning abstract disks or

disks with sentences containing elaborate French puns. By emphasizing simple

shapes and writing, Duchamp created an "anemic" style. (Anemic is

also an anagram for cinema.) In keeping with his playful attitude, he signed

the film "Rrose Selavy", a pun on Eros c'est la vie (Eros is life).

Entr'acte and other dada films were on the 1925

Berlin program, and they convinced German filmmakers like Walter Ruttman and

Hans Richter that modernist style could be created in films without completely

abstract, painted images. Richter, who had been linked with virtually every

major modern art movement, dabbled in Dada. In his Vormittagsspuk (Ghosts

before Breakfast, 1928), special effects show objects rebelling against their

normal uses. In reverse motion, cups shatter and reassemble. Bowler hats take

on a life of their own and fly through the air, and the ordinary laws of nature

seem to be suspended."

Riven by

internal dissension, the European Dada movement was largely over by 1922. Many

of its members formed another group, the Surrealists. While many dadaists

considered Breton to be a traitor to dada, others made the transition directly

into surrealism. After a brief period of what was termed "le mouvement

flou,"(the fuzzy movement) in which the surrealists defined the movement

by reference to the discarded dada, Breton (known as the Pope of Surrealism)

published the first Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924. It was

surrealism's declaration of the rights of man through the liberation of the

unconscious. The goal of surrealism was to synthesize dream and reality so that

the resulting art challenged the limits of representation and perception.

Surrealism abandoned the dada goal of art as a direct transmitter of thought

and focused instead on expressing the rupture and duality of language through

imagery.

The surrealist image could be either verbal or

pictorial and had a twofold function. First, images that seem incompatible with

each other should be juxtaposed together in order to create startling analogies

that disrupt passive audience enjoyment and conventional expectations of art.

This technique was perhaps an influence of Soviet montage theory, with which

the surrealists were familiar. Second, the image must mark the beginning of an

exploration into the unknown rather than merely representing a thing of beauty.

The surrealist experience of beauty instead involved a psychic disturbance, a

"convulsive beauty" generated by the startling images and the

analogies they create in the mind of the viewer.

Germaine Dulac,

who had already worked extensively in regular feature filmmaking and French

Impressionism, turned briefly to Surrealism, directing a screenplay by poet

Antonin Artaud. The result was La coquille et le clergyman (The Seashell and

the Clergyman, 1928), which combines Impressionist techniques of cinematography

with the disjointed narrative logic of Surrealism. A clergyman carrying a large

seashell smashes laboratory beakers; an officer intrudes and breaks the shell,

to the clergyman's horror. The rest of the film consists of the priest's

pursuing a beautiful woman through an incongruous series of settings. His love

seems to be perpetually thwarted by the intervention of the officer. Even after

the priest marries the woman, he is left alone drinking from the shell. The

initial screening of the film provoked a riot at the small Studio des Ursulines

theater, though it is still not clear whether the instigators were Artaud's

enemies or his friends, protesting Dulac's softening of the Surrealist tone of

the scenario. With The Seashell and the Clergyman, Dulac overhauls

narrativity entirely and presents us with pure feminine desire, intercut

against masculine desires of a priest. Above all, Dulac is responsible for

"writing" a new cinematic language that expressed transgressive

female desires in a poetic manner.

Perhaps the quintessential

Surrealist film was created in 1928 by novice director Luis

Buñuel. A Spanish film enthusiast and modernist poet, Buñuel had come to

France and been hired as an assistant by Jean Epstein. Working in collaboration

with Salvador Dali, he made Un chien andalou (An Andalusian Dog). Its basic

story concerned a quarrel between two lovers, but the time scheme and logic are

impossible. Throughout, intertitles announce meaningless intervals of time

passing, as when "sixteen years earlier" appears within an action

that continues without pause." A series of shocking sequences were

designed to challenge any audience: a hand opens to reveal a wound from which a

group of ants emerge; a young man drags two grand pianos across a room, laden

with a pair of dead donkeys and two nonplussed priests, in a vain attempt to

win the affection of a woman he openly lusts after. These are just two of the

more outrageous sequences in the film; perhaps the most famous scene occurs

near the beginning, when Buñuel himself is seen stropping a razor on a balcony

and then ritualistically slitting the eyeball of a young woman who sits

passively in a chair a moment later.

Buñuel and Dali would collaborate on one more film together, the very

early sound picture L'âge d'or (The Age of Gold, 1930), but the two artists

fell out on the first day of shooting, with Buñuel chasing Dali from the set

with a hammer. L’Âge d’or was savagely anticlerical, and the initial

screening caused such a riot that the film was banned for many years before

finally appearing in a restored version on DVD. L'âge d'or loosely follows

two lovers whose passion defies society’s conventions; the film begins with a

documentary on the mating habits of scorpions and ends with an off-screen orgy

in a monastery. Bunuel, when asked to describe L'âge d'or, said that

it was nothing less than "a desperate and passionate call to murder."

Jean Cocteau, a

multitalented artist whose boldly Surrealist work in the theater, as well as

his writings and drawings, defined the yearnings and aspirations of a

generation. His groundbreaking sound feature film, Le sang d'un poète (The

Blood of a Poet, 1930), was not shown publicly until 1932 because of

controversy surrounding the production of Dali and Buñuel’s L'âge d'or,

both films having been produced by the Vicomte de Noailles, a wealthy patron of

the arts.

Dispensing almost entirely

with plot, logic, and conventional narrative, The Blood of a Poet

relates the adventures of a young poet who is forced to enter the mirror in his

room to walk through a mysterious hotel, where his dreams and fantasies are

played out before his eyes. Escaping from the mirror by committing ritualistic

suicide, he is then forced to watch the spectacle of a young boy being killed

with a snowball with a rock center during a schoolyard fight and then to play

cards with Death, personified by a woman dressed in funeral black. When the

poet tries to cheat, he is exposed, and again kills himself with a small

handgun. Death leaves the card room triumphantly, and the film concludes with a

note of morbid victory.

Photographed by the great Georges Périnal, with music by Georges Auric, The

Blood of a Poet represented a dramatic shift in the production of the

sound film. Though influenced by the work of Dali and Buñuel and the Surrealist

films of Man Ray and René Clair, the picture represents nothing so much as an

opium dream (Cocteau famously employed the drug as an aid to his creative

process). Throughout, Cocteau uses a great deal of trick photography, including

negative film spliced directly into the final cut to create an ethereal effect,

mattes (photographic inserts) to place a human mouth in the palm of the poet’s

hand, and reverse motion, slow motion, and cutting in the camera to make people

and objects disappear. For someone who had never before made a film, Cocteau

had a remarkably intuitive knowledge of the plastic qualities of the medium, which

he would exploit throughout his long career."

"Self-taught American

artist Joseph Cornell had begun painting in the early

1930s, but he quickly became known chiefly for his evocative assemblages of

found obj ects inside glass-sided display boxes. Mixing antique toys, maps,

movie-magazine clippings, and other emphemeral items mostly scavenged from New

York secondhand shops, these assemblages created an air of mystery and

nostalgia. Although Cornell led an isolated life in Queens, he was fascinated

by ballet, music, and cinema. He loved all types of films, from Carl Dreyer's The

Passion of Joan of Arc to B movies, and he amassed a collection of 16mm

prints.

In 1936, he completed Rose

Hobart, a compilation film that combines clips from scientific documentaries

with reedited footage from an exotic Universal thriller, East of Borneo (1931).

The fiction footage centers around East of Borneo's lead actress, Rose

Hobart. Cornell avoided giving more than a hint as to what the original plot,

with its cheap jungle settings and sinister turbaned villain, might have

involved. Instead, he concentrated on repetitions of gestures by the actress,

edited together from different scenes; on abrupt mismatches; and especially on

Hobart's reactions to items cut in from other films, which she seems to

"see" through false eyeline matches. In one pair of shots, for

example, she stares fascinatedly at a slow-motion view of a falling drop

creating ripples in a pool. Cornell specified that his film be shown at silent

speed (sixteen frames per second instead of the usual twenty-four) and through

a purple filter; it was to be accompanied by Brazilian popular music. (Modern

prints are tinted purple and have the proper music.)"

Rose Hobart seems to have had a single

screening in 1936, in a New York gallery program of old films treated as

"Goofy Newsreels". Its poor reception dissuaded Cornell from showing

it again for more than twenty years.

Surrealist Cinema's Style:

"Whereas the French

Impressionist filmmakers worked within the commercial film industry, the

Surrealist filmmakers relied on private patronage and screened their work in small

artists' gatherings. Such isolation is hardly surprising, since Surrealist

cinema was a more radical movement, producing films that perplexed and shocked

most audiences.

Surrealist cinema

was directly linked to Surrealism in literature and painting. According to its

spokesperson, Andre Breton, "Surrealism [was] based on the belief in the

superior reality of certain forms of association, heretofore neglected, in the

omnipotence of dreams, in the undirected play of thought." Influenced by

Freudian psychology, Surrealist art sought to register the hidden currents of

the unconscious, "in the absence of any control exercised by reason, and

beyond any aesthetic and moral preoccupation."

Automatic

writing and painting, the search for bizarre or evocative imagery, the

deliberate avoidance of rationally explicable form or style - these became

features of Surrealism as it developed in the period 1924-1929. From the start,

the Surrealists were attracted to the cinema, especially admiring films that

presented untamed desire or the fantastic and marvelous (for example, slapstick

comedies, Nosferatu, and serials about mysterious supercriminals). Surrealist

cinema is overtly anti-narrative, attacking causality itself. If rationality is

to be fought, causal connections among events must be dissolved, as in The

Seashell and the Clergyman.

Many Surrealist films tease us to find a

narrative logic that is simply absent. Causality is as evasive as in a dream.

Instead, we find events juxtaposed for their disturbing effect. The hero

gratuitously shoots a child (L’Âge d’or), a woman closes her eyes only to

reveal eyes painted on her eyelids (Ray's Emak Bakia, 1927), and - most famous

of all - a man strops a razor and deliberately slits the eyeball of an

unprotesting woman (Un chien andalou). An Impressionist film would motivate

such events as a character's dreams or hallucinations, but in these films,

character psychology is all but nonexistent. Sexual desire and ecstasy,

violence, blasphemy, and bizarre humor furnish events that Surrealist film form

employs with a disregard for conventional narrative principles. The hope was that

the free form of the film would arouse the deepest impulses of the viewer.

The style of Surrealist

cinema is eclectic. Mise-en-scene is often influenced by Surrealist painting.

The ants in Un chien andalou come from Dali's pictures; the pillars

and city squares of The Seashell and the Clergyman hark back to the

Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico. Surrealist editing is an amalgam of some

Impressionist devices (many dissolves and superimpositions) and some devices of

the dominant cinema. The shocking eyeball slitting at the start of Un chien

andalou relies on some principles of continuity editing (and indeed on the

Kuleshov effect). However, discontinuous editing is also commonly used to

fracture any organized temporalspatial coherence. In Un Chien andalou,

the heroine locks the man out of a room only to turn to find him inexplicably

behind her. On the whole, Surrealist film style refused to canonize any

particular devices, since that would order and rationalize what had to be an

"undirected play of thought."

The fortunes of Surrealist cinema shifted with

changes in the art movement as a whole. By late 1929, when Breton joined the

Communist Party, Surrealists were embroiled in internal dissension about

whether communism was a political equivalent of Surrealism. Buñuel left France

for a brief stay in Hollywood and then returned to Spain. The chief patron of

Surrealist filmmaking, the Vicomte de Noailles, supported Jean Vigo's Zéro de

conduite (1933), a film of Surrealist ambitions, but then stopped sponsoring

the avant-garde. Thus, as a unified movement, French Surrealism was no longer

viable after 1930. Individual Surrealists continued to work, however. The most

famous was Buñuel, who continued to work in his own brand of the Surrealist

style for 50 years. His later films, such as Belle de jour (1967) and Le charme

discret de la bourgeoisie (1972), continue the Surrealist tradition." In

1947 Hans Richter released Dreams That Money Can Buy, seven short episodes that

examine the unconscious, written by and featuring Richter, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp,

Fernand Léger, Max Ernst (1891–1976), and Alexander Calder (1898–1976). Besides

Bunuel's work, this is the last official surrealist film.

Refer:

Comments

Post a Comment